Scholarly Communications: Where Advocacy and Social Community Intersect

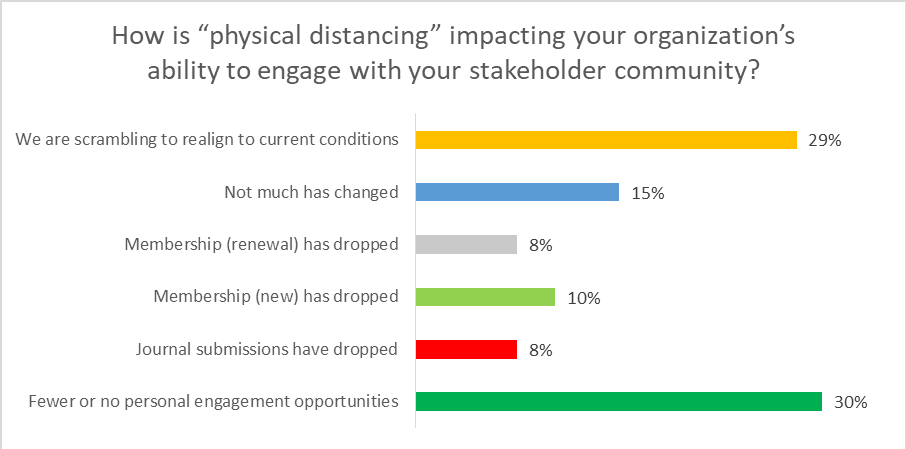

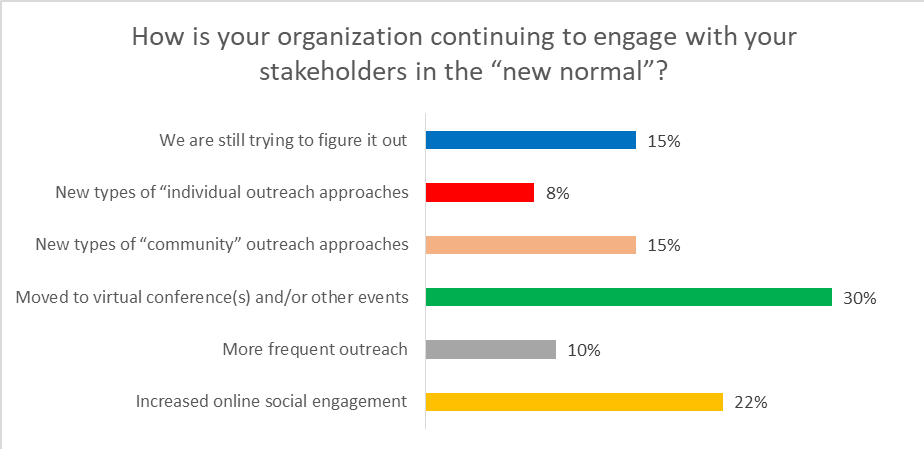

How is physical distancing impacting your organization’s ability to engage with your stakeholder community? And how is your organization continuing to engage with stakeholders in the “new normal”

These two questions kicked off Session 3 of Cactus Communications’ recent Stay Home, Stay Connected, Keep Growing virtual conference. The session entitled Scholarly Communications: Where Advocacy and Social Community Intersect was designed to address how various organizations, with very different stakeholder communities, have adjusted mission-driven outreach strategies to maintain relevant purpose in the current COVID-19 pandemic disruption. As you can see from the charts below, we quickly established via a couple of online polls that the most popular answers to the first question were “We are scrambling to realign to current conditions”and there are “fewer or no personal engagement opportunities,” with 29% and 30% of respondents voting for these. In answer to the second question 30% told us that their organization has “moved to virtual conferences and/or other events,” while 22% said that they have “increased online social engagement.

With this perspective in mind, I and my fellow panelists, Angela Cochran (American Society of Civil Engineers), Lisa Janicke Hinchliffe (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign), and Elizabeth Landau (American Geophysical Union), with panel organizer and moderator Donald Samulack of Cactus Communications, shared our own experiences of what it means to build a social community in a world of physical distancing, conceptually and practically. The four of us collectively represent a broad range of stakeholders — university libraries and, by extension, researchers (Lisa), societies and the researcher/practitioner community (Angela), societies and researchers, policymakers, and the general public (Liz), and the professional organization/open research infrastructure community (me). So, at the conceptual level, what does community look like for each of us, how do community members see themselves, and why and how do they want to participate? And in practical terms, what does this mean for how we engage with them during the COVID-19 pandemic — what needs to change and what will stay the same?

Let’s start with Lisa, who pointed out that many researchers have stronger ties to their discipline community (including their professional society) than their institutional community. Libraries, of course, sit at the intersection of the two, and work with both; the shift to digital has enabled them to focus on developing services that are about using information rather than accessing it — data management services, text mining services, and more. However, for some disciplines, access to print information remains essential, even during the pandemic, and many institutions are still finding ways to support this. Lisa also noted that, while characterizing libraries as being virtual spaces that people can also visit in person, the pivot to remote only access due to the pandemic has highlighted some of the underlying research infrastructure challenges around access to content. Turning to what is happening in practice, Lisa highlighted her ongoing research with Christine Wolff-Eisenberg on US Academic Library Response to COVID19 - more than 800 US institutions have shared their experiences. She also highlighted the fact that librarians themselves are very much part of the research infrastructure. At UIUC, librarians are assigned to specific departments or colleges so that they can build personal relationships with faculty and students in order to better understand and meet their individual needs through a customized service — from when and how a faculty member wants to engage to acquiring the content anyone needs in the format they require.

The civil engineering community is incredibly broad and heterogeneous, which, as Angela pointed out, makes it challenging to serve their often differing needs. Her society achieves this in part through sub-communities, including by sub-discipline. She noted that this can be complicated by the fact that some sub-disciplines have more in common with non-engineering disciplines, such as environmental engineers, who are more closely aligned with chemists than with, say, structural engineers. ASCE’s sub-communities are also segmented across sub-disciplines, for example, by demographic (geography, career stage, etc), and organization type (industry, academia, etc). It’s critical to identify topics that cut across all these groups in order to bring them together: for example, sustainability, reliability, risk, and — yes! — standards, since the need for them is often identified by academics, but they are used by practitioners. Angela noted that ASCE also plays a role in addressing “translation” issues between their sub-communities. As the society starts to transition from emergency status to the new status quo, there’s an opportunity (and need!) for experimentation. For example, whereas previously conference proceedings were an important component of ASCE’s program, if there’s no conference there are no registration fees to help pay for publication of those proceedings, so they are thinking about alternative outputs. Their goal is to make sure the right resources are available — whether that be a new weekly professional development webinar to help with immediate needs, or daily instead of weekly podcasts — and to drive people to them on their own schedule.

AGU’s communities include members, policy-makers (mostly federal US but also local and international), local communities, and the media. Liz told us about some of the great programs she and her team have developed to engage with them, including supporting outreach by members through the Voices for Science program, working on a one to one basis with policy-makers to share science to inform their decision-making, and working to help scientists engage with their local communities, for example, through the Thriving Earth Exchange program. They do this via a mix of specialists and generalists. Much of their programming was formerly focused on in-person activities, so they have needed to rethink a lot of what they do. For example, the Voices for Science program usually brings 40 scientists together for two days of in-person training in March. After considering all the options, this year they decided to make it virtual, which meant thinking again about the goals of the program and the needs of scientists involved. Liz also shared some wonderful examples of how her community has continued to advocate for science even under lockdown! These included one member who held a Netflix watch party of a movie about plastics pollution, followed by a discussion with her guests. Another has created her own version of rainbows in windows — putting a new science fact up on her door every week.

NISO is somewhat different from UIUC, ASCE, and AGU; we are a membership organization, but not a society, and our members are themselves organizations, not individuals. Standards are an essential component of the overall research infrastructure, which enables the level playing field needed for individuals organizations to create tools and services that support research and researchers. Our goal is to bring different types of (sometimes competing!) organizations together to achieve common goals and address common problems through the development of community standards. While this typically requires an element of compromise, it also means that everyone gets most of what they need. Finding the right people within our stakeholder organizations can be challenging, especially as different elements of the research infrastructure are often siloed, but the infrastructure can only really be effective in combination. We therefore need to continuously communicate its value for the individual researcher, the organization, and the broad community. In practical terms, as a small, not-for-profit, we are very reliant on our wonderful volunteers, some of whom are understandably quite distracted at present. However, since more than half our (tiny!) staff were already working from home, almost all our work is done remotely anyway, and our educational program is mostly virtual, in many ways it has been business as usual for NISO. And, as our still relatively new, first Director of Community Engagement, it’s exciting to have an opportunity to develop a born-digital community engagement program.

To end the webinar, Donald turned the tables and asked us how researchers are adapting to the “new normal.” Lisa has seen a huge variety of responses, from those experiencing no problems at all to those who are unable to do anything. As she noted, equity is a big issue, with an increasing divide between researchers who still have the resources and support they need to continue their work, and those who cannot. In particular, there are some worrying trends in terms of gender effects, as well as lack of internet access, for example, for some graduate students. ASCE is still waiting to see what the impact will be on their members, according to Angela. The organization is closely monitoring the number of submissions, but there has been no dip so far, with researchers still able to work on modeling/data, for example. However, she noted that the ongoing lack of access to labs and collaborative opportunities — both locally and internationally — is a very real concern. From Liz’s perspective, on the plus side there has been a very encouraging increase in online advocacy, with more researchers than ever engaging with policy-makers and others online. But on the flip side, she also sees that isolation is taking a toll on many scientists’ ability to engage and do their work.

Many thanks to Donald and to Cactus Communications for the opportunity to participate in this portion of a very successful virtual conference; session-specific recordings will be available shortly on the conference website.